Trad Climbing Ethics: A Very Brief History - By Ben Moon

Most people probably associate me with sport climbing and bouldering, but when I left school in 1982 to climb full time, sport climbing didn’t exist in the UK and bouldering was something you did when you couldn’t go roped climbing. When I moved to Sheffield in 1983, I fell in with a young group of climbers pushing the limits of British climbing — people like Jerry Moffatt, Andy Pollitt, Chris Gore, and Ron Fawcett. Rock climbing was on the verge of massive change, but at that time we were all what you might now call trad climbers. Most routes had no in-situ protection and required nuts and cams for safety. Sport climbing, redpointing, headpointing, and on-sighting were terms that didn’t yet exist. You started from the ground, placing protection as you went, and tried to reach the top without falling. If you did fall, you usually lowered to the ground, rested, and tried again, leaving your ropes clipped into your high point — a style known as a yo-yo. We’d even count how many yo-yos it took to complete a route. The ultimate goal, of course, was to climb it ground up, first try, without falling — what we called a flash, since the term on-sight wasn’t yet in use.

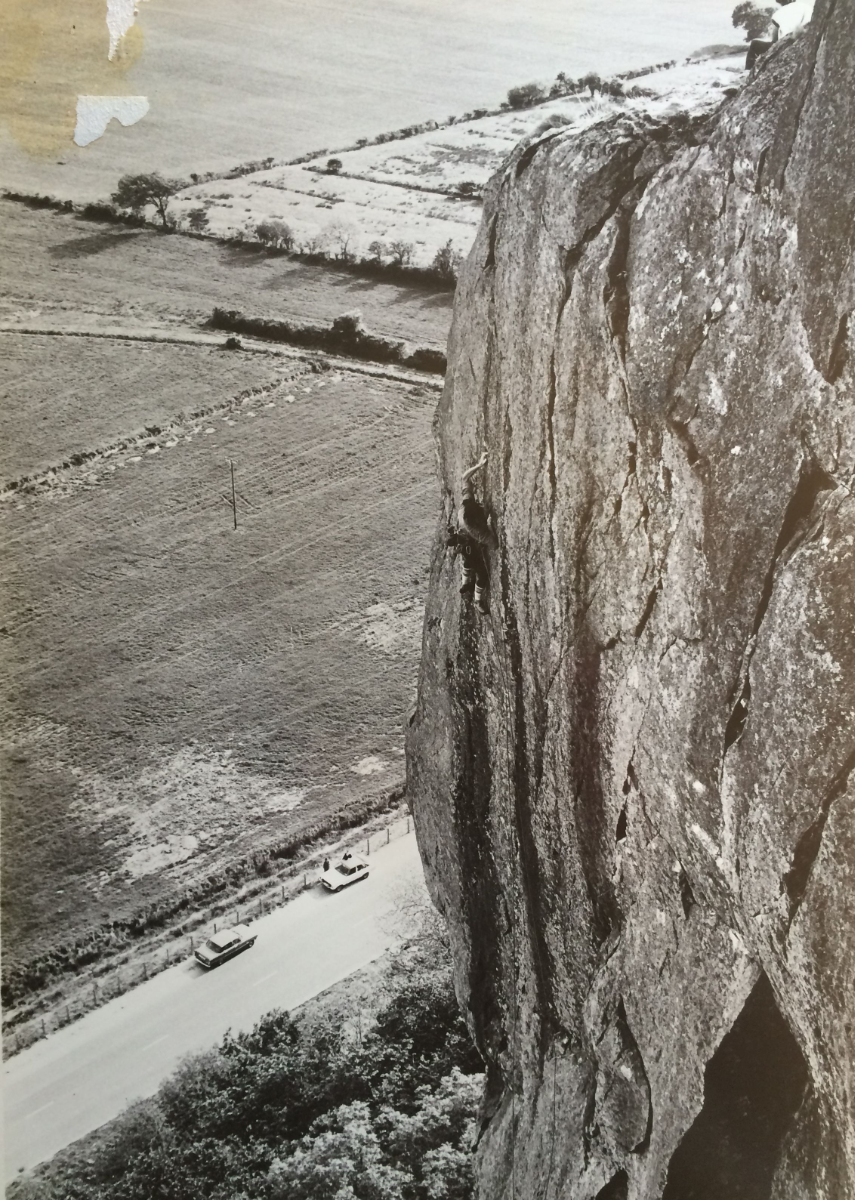

Strawberries | Tremadoc - 1984

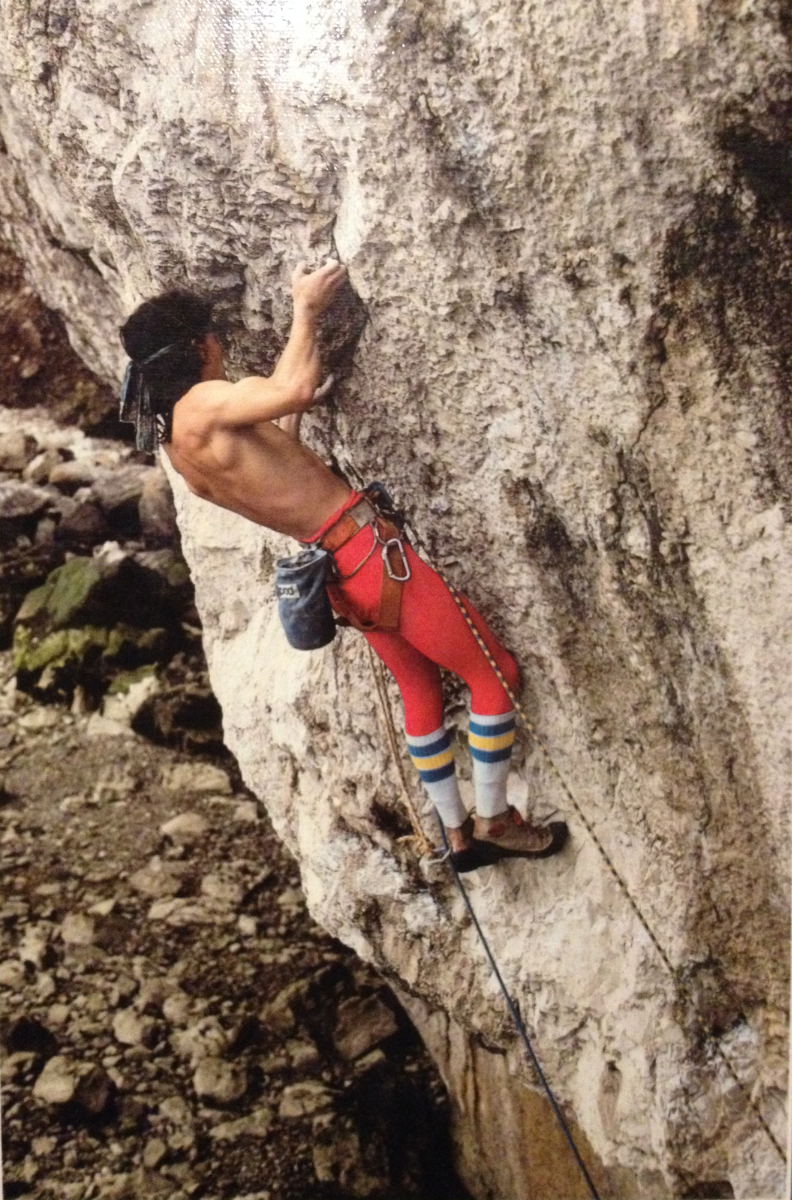

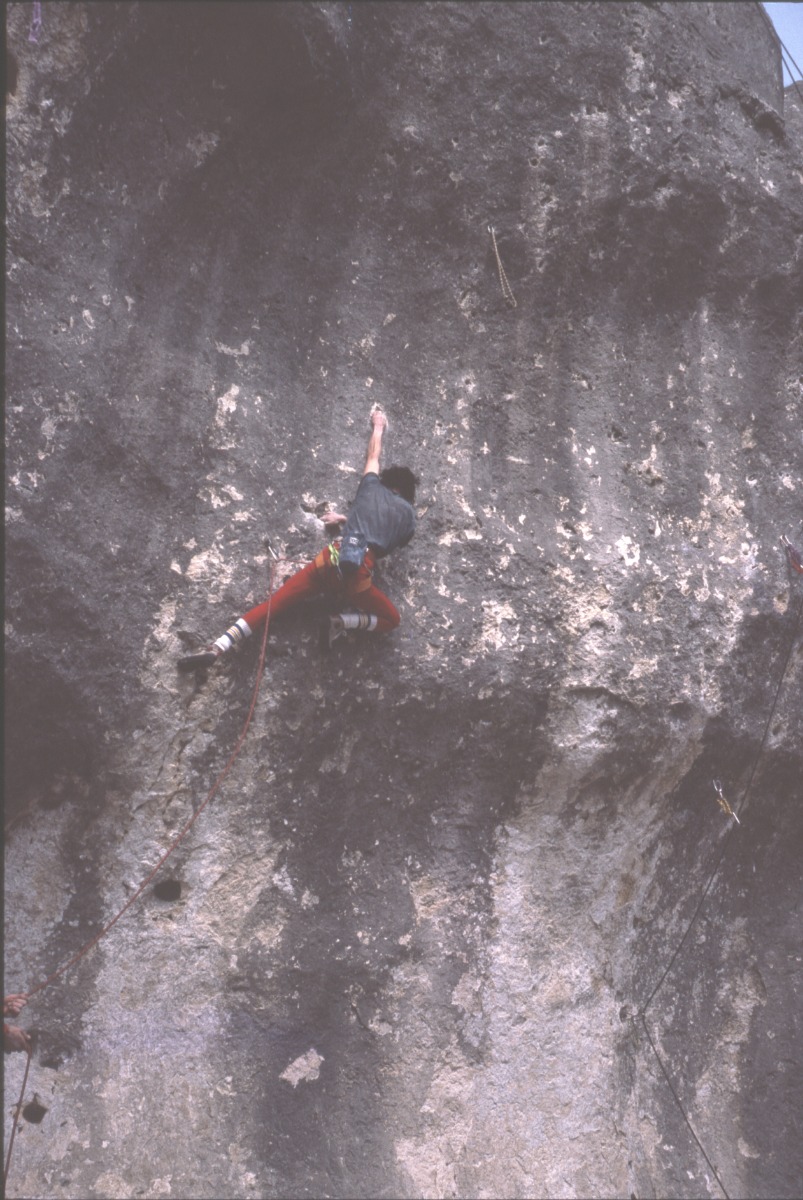

I first heard the term on-sight in 1984, on a trip to France with Jerry. The French were impressed by some of his on-sight ascents — climbing a route first try with no prior knowledge — as opposed to a flash, which meant first try with knowledge. Before that, we hadn’t really distinguished between the two, though an on-sight was clearly the greater achievement. Both were highly prized, but the on-sight was the pinnacle. To climb hard on- sights you needed exceptional strength and endurance, but perhaps more importantly, the ability to read the rock and find the most efficient sequence. On trad routes you also needed the skill to place your own protection and keep a cool head. As routes got harder, we took more yo-yos and began dogging moves — working specific sequences. Dogging soon became controversial. If you had the legendary American climber John Bachar belaying, you wouldn’t get the chance — he’d lower you off before you could even try! Some saw dogging as cheating. On that first trip to France in 1984, while the French were working entire routes and then redpointing them, we were still trying to climb ground up. It was a clash of styles and ethics. I think the French saw our yo-yo tactics — falling off, working sections, then leaving ropes clipped — as cheating. Later that year, after returning from France, I bolted what became Statement of Youth. I climbed it ground up, yo-yo style, leaving my ropes clipped at the high point after each attempt. It took five days, and when I finally linked it in one push my ropes were still clipped into the last bolt. Climbing hard routes ground up, with or without knowledge, is incredibly inefficient — which is why, in the mid-80s, we adopted the French redpoint style. Sport climbing in the UK was born. So how does this all relate to trad climbing? As new trad routes became rarer, harder, and more dangerous, first ascensionists began adopting the French approach — and headpointing was born. Headpointing is basically redpointing a trad route: you can practise it as much as you like, but the lead must be a clean ascent from the ground, placing all gear as you go. If you fall, you must pull your ropes and strip the gear before trying again. Ethically, it’s clear- cut, and like redpointing, it allows climbers to push into harder territory.

Statement of Youth | Lower Pen Trwyn

Initially, headpointing was confined to cutting-edge new routes, but now it’s common at all levels — and why not? It opens up many routes that might otherwise be too dangerous or unrealistic. But has something been lost? Has the rise of the headpoint taken away part of what makes traditional climbing special?

For me, on-sight climbing — whether sport or trad — remains the purest style and the truest measure of a climber. What first captivated me about climbing, even as a seven-year-old, was the excitement and sense of adventure. Nowhere is that feeling stronger than when you’re on- sight climbing into the unknown with a rack of wires. This isn’t to denigrate headpointing or redpointing — the latter occupied much of my career — but it would be sad to lose the skills and mindset required for on-sight trad climbing, especially when the UK has some of the best and most varied trad climbing in the world. In terms of style, most would agree that the on-sight ascent is the pinnacle. But what comes next? What happens once a fall ends the on-sight attempt? The excellent Gogarth North Ground Up guidebook puts it clearly in its article A Question of Style: “As far as first ascents go, the ideal is an on-sight ascent — stepping into the unknown, route finding and cleaning as you go. Once a fall has brought an on-sight attempt to an end, then ground up is considered the next best thing.”

Chimpanzedrome | Le Saussois - 1984

Gogarth has always had a strong ground-up tradition, and headpointing first ascents there was — and still is — frowned upon more than elsewhere in the UK. Although the above quote is about first ascents, it applies to everyone. On-sight is the ideal; ground up is next best. Once the on-sight is gone, how you continue depends on the route, its character, and what style you’re personally happy with. One of the great things about climbing is its lack of rules — all that really matters is that we look after the environment and are honest about what we’ve done. Honesty is especially important for first ascents. Perhaps it’s generational, but once the on-sight is gone, I’m happy trying for a yo-yo ascent. A better style would be to pull the ropes before trying again — or better still, to pull the ropes and strip the gear — but I don’t do this and don’t see the logic. I’ve already fought my way to that high point, placing my gear as I went, so why start again? Some may call that poor style, but at the end of the day, you do what you’re comfortable with — as long as you’re honest about it.

Perhaps a hierarchy of trad climbing styles would look something like this:

- Ground up, on-sight — climbed from the ground with no falls and no prior

knowledge. - Ground up, flash — climbed from the ground with no falls but with prior

knowledge. - Ground up with falls, pulling ropes and removing gear — essentially a redpoint.

- Ground up with falls, pulling ropes but leaving gear in place — not quite a

redpoint, since placing gear adds a major challenge. - Ground up with yo-yos — leaving gear and ropes clipped to the high point.

- Headpoint — practising the route on top rope before leading it, placing all gear as

you go.

King Rat | Craig an Dubh Loch

All of these can still be classed as clean, free ascents — climbs completed in one push, from bottom to top, without weighting the rope.

Looking back, I feel lucky to have started climbing in a time when the rules were still being written. We experimented, argued, and learned from each other, but the motivation was always the same — to challenge ourselves and experience adventure on the rock. However the styles evolve, I hope that sense of honesty and discovery stays alive for future generations.